Abbey of Genesee

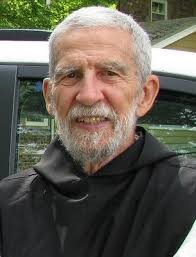

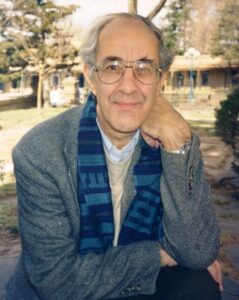

In the last few weeks of his seven months stay at the Abbey of Genesee, Henri Nouwen discussed in a session with the Abbot John Eudes Bamberger how much calmer he felt, less restless and less compulsive and freer. He attributed this to a gradual distancing which had allowed him to see his inner compulsions, and, and let some of them go. Nouwen quotes the experience of a French priest who after 15 years of hearing confessions had learned two things: “People are not very happy, and we never grow up”. The time in the monastery and meditation meant that Nouwen had shifted part of his compulsive behaviour patterns, especially the behaviour that Bamberger called an “ought” compulsion.

‘… a way of being in which everything is experienced in terms of an “ought”. I ought to be here, I ought to think such and such, etc. This way of being has many levels and touches many aspects of the personality. … the “ought modality” is closely tied with the identity struggle. As long as I am constantly concerned about what I “ought” to say, think, do, or feel, I am still the victim of my surroundings and am not liberated. I am compelled to act in certain ways to live up to my self-created image. But when I can accept my identity from God and allow him to be the centre of my life, I am liberated from compulsion and can move without restraints.’

Six months after Nouwen had left his long retreat at the Abbey of Genesee and his spiritual direction meetings with the Abbot, he confronted what he describes as the greatest and hidden illusion that he would after the seven months be a different person. Someone more integrated and spiritual, more virtuous and compassionate, more gentle and joyful and more understanding. He had believed that his restlessness would stop and his tensions subside under a peaceful lifestyle, and all his mixed feelings and ambiguities turn into a single-minded commitment to God. But none of this came about, and he adds, nor would it if he had stayed a lifetime as a Trappist monk. The reality is rather to be able to praise God in the midst of all the usual problems of what it means to be human.

‘I had known this all along, but still I had to return to my old busy life and be confronted with my own restless self to believe it. … some of my most humbling experiences took place after my return. But they had to take place to convince me once again that I cannot be my own exorcist, and to remind me that, if anything significant takes place in my life, it is not the result of my own “spiritual” calisthenics, but only the manifestation of God’s unconditional grace.’

Nouwen asks himself why he went at all to the Abbey, and is able to answer that it felt it was the right place to be, and where he was left with a memory of a glimpse of God’s graciousness when in solitude: ‘the ray of light that broke through my darkness, the gentle voice that spoke in my silence, and of the soft breeze that touched me in my stillest hour.’

A memory that can dispel false dreams and point in the right directions.