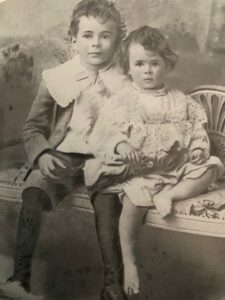

Wilfred Bion aged about 6 and his sister

How we experience religion as children, or not, plays an influential part in our later spiritual development as adults. I know myself that the Congregational minister leaning over the edge of the pulpit and yelling, (probably speaking loudly), about not provoking the wrath of God had a long-term effect on me. This was compounded by having been told that the sound of thunder was God walking up and down in heaven very cross – with me. It’s easy to see how the idea of the punishing God became firmly embedded. But, then there was Jesus who wasn’t cross, but instead meek and mild, and to whom I prayed every night to make me a good girl and to bless everyone I knew, even those I didn’t like. What to make of it all?

It’s easy to see why it’s a relief to let go of that sort of messaging as soon as possible. But it does mean that to develop an authentic religious faith and a meaningful spiritual life most of the old early messages have to be confronted and reworked – seen for what they are, and why they were so powerfully taken in. Then new experiences can be integrated, and so faith and spirituality as an adult start to look a bit different.

In the next few posts, I am going to look at different people’s experiences of their childhood religion and spirituality. The influential psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion, who died in 1979, shared his deep, almost mystical insights into the human condition and what can happen between people in intensive psychotherapy. In his autobiography, he describes some of his early religious (mis)understandings. Brought up in India in the days of the British Raj, he was largely looked after as a small child by an ayah (an Indian nanny), before being sent back to England to boarding school at the age of 8.

Bion begins his autobiography with the family crest: Nisi dominus frustra – without God there is no purpose. Underneath he quotes from Psalm 127 verse 1: ‘Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it; except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain.’ He remembers singing in the evening with his mother and sister the hymn ‘there is a green hill far away, without a city wall’. He writes:

‘– so green compared with the parched burning India of the daylight that had just finished – and its tiny jewelled city wall. Poor little green hill; why hadn’t it got a city wall? It took me a long time to realize that the wretched poet meant it had no city wall, and longer still to realize he meant – incredible though it seemed – that it was outside the city wall.’

His parents kept absolute religious principles that included tolerating no deception, and as a child Bion was often reproached for telling lies. In one incident, he describes fighting with his sister, and replying with a lie that he was doing ‘nothing’ – though it was quite clear that he had boxed her ears as she was ‘bawling’ and blaming her brother.

‘“These children’ said my mother … you’re both as bad as each other!” Up to that point I had fancied that her screams were abating. “Renew a right spirit within me”, but if that was my unspoken prayer it had been wrongly addressed. Her screams were renewed. We were separated.’

Unable to remember why he had decided to punish his sister for earlier wrong doing, which was actually the girl repeating the word ‘lavatory’ in a ‘rude’ way, and, in Bion’s view as the elder brother, not getting sufficiently told off, Bion was given ‘a good beating’ by his father, who was angry with the boy, turning his eyes fiercely on him.

‘From that day on I hated them both “with all my heart and all my soul for ever and ever. Amen.” A few minutes? Seconds? Years? Later I had forgotten all about it; so had they. But as no doubt they suspected I had learned my lesson and so had my sister. So had my parents for they too seemed uneasy, especially when I shrank from them and kept as far away from my sister as possible. “Why don’t you two play together?” my mother would ask in a puzzled way.’