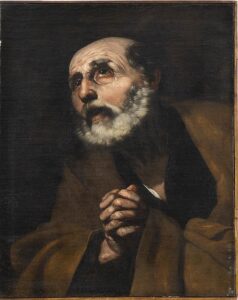

St Peter weeping by Jusepe de Ribera early 17th century

Crying sometimes feels like letting go of self-control – it can be awkward in public – that’s why it’s easier to cry on one’s own. As a spiritual practice it is directly linked to giving up this fantasy of self-control, for although we might think that we are in control that is illusory, yet giving up the idea of being control is real, and so we weep.

Isaac of Ninevah, also known as Isaac the Syrian, wrote about the three causes of tears as: love of God; awestruck wonders at God’s mysteries, and humility of heart. He saw these ‘holy tears’ as progressing from one stage to another and acting as a sign of our transformation. The tears show that we are being born into sacred time which Maggie Ross describes as, ‘not only the interpenetration of time and eternity, but even a reversal of time as we know it’. I think this means we are somehow being moved into a different level of consciousness, something definitely outside of self-control.

There’s quite a bit of crying in the bible: in the Old Testament tears of repentance, tears of lamentation, tears of sorrow. The prophets weep: Isaiah “drenching” with tears those for whom he prays, Jeremiah who was known as the weeping prophet comparing his eyes to a fountain. Yahweh weeps over His errant people. Israel weeps in repentance, and then God cannot resist. In the New Testament, Christ weeps, touched by the sorrow of Martha and Mary at the death of Lazarus. Jesus’ feet are washed with tears of repentance and love. Peter weeps bitterly after denying his Lord three times and meeting Jesus’ sorrowful gaze. Paul tells the Ephesians he has been crying continuously for three years over their behaviour.

Many saints also describe their crying: Catherine of Siena whilst in ecstasy wrote what Christ told her about tears, and Ignatius was advised that his copious tears could harm his eyesight. Ephrem was said to weep continuously, and Thomas Aquinas insisted tears relieved pain. “Tears are the heart’s blood,” said St. Augustine, referring to the tears of his mother Monica, tears which purchased his conversion. St. Augustine, in his Confessions wrote:

“When deep reflection had dredged out of the secret recesses of my soul all my misery and heaped it up in full view of my heart, there arose a mighty storm, bringing with it a mighty downpour of tears”.

More recently Padre Pio says that tears are “the work of God in you”, and as a novice, took to placing a large handkerchief on the floor in front of him: his constant tears were leaving traces on the stone floor of the choir where he prayed. Pope Francis says the gift of tears “prepare the eyes to look, to see the Lord.” “It is a beautiful grace,” he says, “to weep praying for everything: for what is good, for our sins, for graces, for joy itself… it prepares us to see Jesus.” St. John Vianney could not speak of sinners and sins without weeping and when asked, “Fr. Vianney, why do you cry so much?” The answer was given, “Because you don’t cry enough.”

This links to therapy where crying by the person being seen is common – a safe place to express sadness and hurt, but a study shows that a significant proportion of trainee therapists also reported crying in support of the therapeutic process. However, as experience develops the therapist is usually able to feel the suppressed emotion, but in a way that it can be held and then later conveyed to the client when they are ready to open themselves to the feeling themselves.