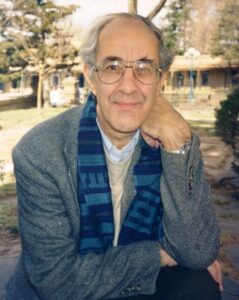

Henri Nouwen

We seem to get easily caught in strange paradoxes: complaining about being too busy, but feeling uneasy when there’s nothing much on and no demands are made. Feeling pressurised by emails, and yet desolate if there aren’t any. Fretting about being asked to do things, but if no one asks what then … tired of company, but what if there was none?

‘The more I became aware of these paradoxes, the more I started to see how much I had indeed fallen in love with my own compulsions and illusions … While realising my growing need to step back, I knew that I could never do it alone.’

This realisation by Henri Nouwen led him to talk with John Eudes Bamberger psychiatrist and theologian and then monk at the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani, and to visit Bamberger regularly for spiritual direction. After Bamberger became Abbot at the Abbey of the Genesee in upstate New York, Nouwen went to live there for seven months as a temporary Trappist monk. This was in 1974, and Nouwen kept a diary of his experiences.

The paradox of wanting solitude, but also needing others is one that Thomas Merton also knew about. A gregarious personality plus loving his connection with people through mail and books, as well as enjoying people visiting him in the hermitage, led to a constant tension. In the last year of his life, Merton was searching for a place to really be alone with God and held the tension of this with its opposite, which was compassion for those whom he met or heard about.

For Henri Nouwen, a paradox that quickly emerged as he began this step back by taking his extended retreat at the Abbey of Genesee was the desire to live in the presence of God. This was running alongside all the ideas in Nouwen’s head about what else he wanted to do: ideas to write about, books to read, skills to learn, what he wanted to say to others. He calls these wishes ‘ego-climbing’ as distinct from ‘selfless climbing’.

This distinction he got from Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig who describes that whilst ego-climbing and selfless climbing may look the same, there is a clear difference:

‘The ego-climber is like an instrument that’s out of adjustment. He puts his foot down an instant too soon or too late … he’s here but he’s not here. He rejects the here, is unhappy with it, wants to be further up the trail but when he gets there will be just as unhappy because then the it will be ‘here’. What he is looking for, what he wants is all around him, but he doesn’t want that because it is all around him. Every step’s an effort both physically and spiritually because he imagines his goal to be external and distant.’

For Nouwen came the realisation that he did not SEE that God was all around as he was too busy trying to look ahead, overlooking the God who is so close to each one of us. And perhaps being stuck with this tension was the way to really understand it.