One of the subjects that Thomas Merton spoke about in his lectures to the novices at the Abbey of Gethsemani was the legacy left by Maximus the Confessor – a theologian, Christian monk and scholar. Maximus was born in AD 580 in the Byzantine Empire and there are different accounts of his early life, but he arrived in North Africa as a monk in 630 and from which time many of his writings are dated, and his reputation had developed. Maximus opposed monothelitism a theological doctrine, first proposed in 622 and endorsed by the Emperor Heraclius, that argued that Jesus Christ, though having two natures (divine and human), had only one will. As a result of opposing this, Maximus was arrested in Rome with two of his disciples and sent to Constantinople. At his first trial in 655, Maximus was first of all accused of treason, then. accusations turned to theological matters, in which Maximus denied that any Emperor had the right to encroach on the rights of priesthood and define dogma. Maximus was exiled to what is now the Turkish Bulgarian border where further attempts followed to break his resolve.

When they failed, Maximus was tried again in Constantinople, tortured, had his tongue and his right hand – the instruments with which he had defended Orthodoxy (or to his judges proclaimed heresy) – cut off, and exiled to Lazica, now western Georgia where he died, over eighty years old, on 13 August 662. He died abandoned, except for his two disciples. Within twenty years the teaching for which he had given his life – the doctrine that Christ had two wills, a divine will and a human will – was vindicated at the sixth Ecumenical Council, convened at Constantinople in 680, though no mention was made there of the great confessor of Orthodoxy, St Maximus.

Maximus’ uppermost concern was for the life of prayer and engagement with God; it has been written that he was able to draw disparate things together in a profound and compelling way, and whilst many of his ideas can be traced back to early Christianity and indeed even earlier sources, with links to Evagrius and Neoplatonism, his thinking feels surprisingly relevant and important not just for the twentieth century when Merton was teaching but also for the twenty-first century.

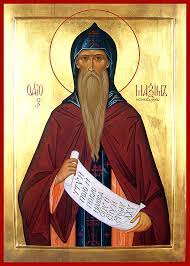

St Maximus the Confessor

Merton emphasises the contribution by Maximus to ‘the great mystical tradition’. Maximus saw that this ‘is not separated from the dogmatic and moral tradition but forms one whole with it. Without mysticism there is no real theology, and without theology there is no real mysticism.’

Merton spoke to the novices about Maximus’ teachings on contemplation and on the cosmos using the term ‘theoria physike’. Merton explains this as ‘a contemplation according to nature (physis). It is also a contemplation of God in and through nature, in and through things He has created, in history … It is wisdom in all its forms, the gnosis that apprehends the wisdom and glory of God, especially His wisdom as Creator and Redeemer’. It is in the spirit of Scripture and not in the letter; in the logoi of created things, not in their materiality; in our own inmost spirit and true self, rather than in our ego; in the inner meaning of history and not in its externals (in other words the history of salvation, and the victory of Christ); and in the inner sense of the divine judgements and mercies (not in superstitious and pseudo-apocalyptic interpretations of events).