It has been said that mystical surrender always includes aspects of masochism – it seems especially so when particular practices and techniques are encouraged to experience bodily suffering as a way to control the sense of self. So ascetic practices such as fasting or deliberate suffering towards the body can be rationalised as a means to an end, but are clearly masochistic. Similarly, the longing for self-annihilation through absorption in union with God is about using suppression and repression as a way of controlling the self. This is also masochistic as it is a denial of our God-given personhood. It is surely a deliberate sabotaging of our life’s journey, and our learning from all life’s experiences in a mistaken belief that God is looking for ‘an empty clone’ or a ‘shadow person’.

All religions demand some degree of surrender – that in the letting go of control there is a freedom. But what is it that is being surrendered? My suggestion would be that contemplation offers us the answer to this which is about surrendering our sense of being different to others – our narcissism – our self-importance. Contemplation certainly involves setting aside time and conscious ‘everyday’ thinking to spend time apart and alone with God – this is a different activity from masochistic surrender and one where the time in quiet appears to enrich and enable us to live in better harmony with one another and the world.

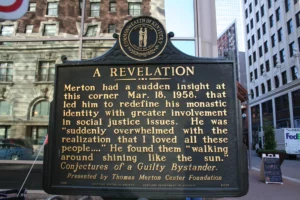

Thomas Merton in The Seven Storey Mountain displays a fair bit of masochism which is linked to a deep sense of self-loathing (in itself a preoccupation with being especially sinful etc.). Following his conversion Merton writes of his guilt – his feelings of holding himself responsible for wrongs and the deep need to make amends and so on. But he does seek a real humility in his personal life. By the time of the famous Fourth and Walnut experience after a decade and a half in the Abbey, Merton is able to give thanks for being ordinary – like everyone else – not especially good and nor especially bad.

In Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander Merton writes: ‘it was like waking from a degree of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world, the world of renunciation and supposed holiness’. This is I think awaking from a fantasy of masochism – that our suffering and separateness from others leads to union with God. Instead, Merton sees that such differences of holiness are illusory. We are all human and party to what he calls ‘the sorrows and stupidities of the human condition’. The incarnation was about God joining in with us – not to make misery and suffering the way out to be with him. God is already in union with us so that we ‘are all walking around shining like the sun’. Being open to ourselves is about vulnerability and that is a form of surrender, but one where authentic relationship with God can develop – masochism suffering and self-annihilation is the closure of that. Merton’s insight was about being united with and not separated from the rest of the human race, and in that connection to one another so there is connection with the incarnate God.