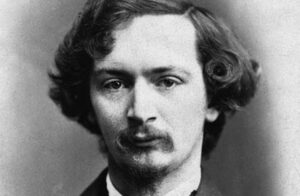

Vera von der Heydt

One of the problems of life is how to get to know oneself, and how to relate to and accept who and what one really is. This is the courage to be authentic, living with the knowledge of both the good and bad present in each of us. Only then is it possible to live in the present moment.

I like the way that Vera von der Heydt – an early follower of Carl Jung, and a pioneer in the study of the relationship between psychology and religion, expresses how important it is to recognise the ‘conditionings and prejudices which keep one in a state of unconsciousness’. She understands that we can’t do this on our own and need help – it might come from a book, or a friend, therapist, or a random stranger, and ‘chance may well cast a glimmer of light on it’:

‘We need another human being to encourage us to continue our searchings when we are in the wilderness. …Sometimes, however, one is too identified with and unconscious of the nature of one’s problem to be able to listen nor to see the key which could open the door to one’s prison.’

Von der Heydt was born in Berlin to a Jewish father and a mother who was half German and half Irish; her parents had high expectations of achievement and success. As a child she felt unable to identify with any other member of her family, aware of ‘the conflicting strains within myself … and my racial and spiritual “otherness”’. Seen as delicate in her early childhood, and considered stupid but pretty, she was sent off at the age of 12 to a school where she was told it was vital to learn to think. She liked the school very much, and describes a significant experience when she asked to see the headmaster to find out whether he believed in the immortality of the soul. He advised her to read books, and she began to read the mystics, Jewish, Christian and Indian, because of this, ‘I became more and more aware of another dimension’.

After an unsuccessful early marriage led to divorce, von der Heydt felt that she continued to live in a state of unconsciousness, until gradually waking up to a realisation that what she had been looking for within herself was an inner power ‘pushing me out of a collective, conditional environment into shaping my own life.’ With Hitler’s rise to power, she emigrated to Britain to live in London and work as a secretary:

‘I had ample time to think about things, about the dreadful outer events and the reaction of various countries and various individuals to the Fascist mass movement and to the violence that was unleashed and deliberately fostered. I began to look at myself, at my own violence and wish to retaliate, my hope of avenging myself on those who had killed – murdered – people I loved.’

Full of inner turmoil, she spent time sitting in churches. In the Brompton Oratory she sat speaking to the figure of Jesus and in her mind heard him speak to her. She then knew she had to become Catholic – ‘Actually I did not “become” a Catholic, for I realised that I had been one all my life’. Attacked by a number of people who couldn’t understand this decision given the dogma and the crimes of the church over the centuries; von der Heydt only knew that she had stumbled across her truth. Later, framing it in Jungian terminology, she understood that an archetype had been activated and a symbol had come to life within her.