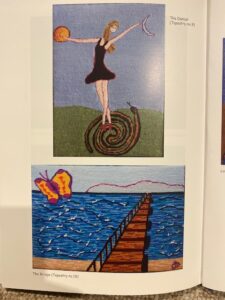

Two of the tapestries – the top one called The Dancer and the lower The Bridge

One of the ways in which Marika Henriques began to be able to balance the light and the darkness that arose in the therapy was through embroidery. She had initially drawn and painted, and she had written too, but she writes that she wanted to repair by working through the fragments of her experience stitching things together to make into one.

‘Change can sometimes be sudden and swift or it can be imperceptibly slow. Like my tapestries where each final image appeared (I counted once) through twenty-four thousand small stitches, similarly my becoming more myself came about with small, hardly discernible movements. In my case, change took time. Two decades.’

All was done through image, and this confirmed for her that healing happened through the imagination. The whole experience of creativity – drawing, writing, stitching became healing and transformative, so that Marika Henriques could say: ‘The effects of hiding no longer ruled my life. … When I finished stitching, I felt that I had fulfilled a scared responsibility’.

However, five years after completing the tapestries and believing that she had completed her personal healing journey Marika Henriques began to have Holocaust dreams again. The dreams became part of a sequence – they were instructive dreams with a clear thread running through them; often there were themes forgetting and remembering and losing and finding. In one there was a stark message:

‘I have to return home from abroad, I am in great danger. A rescue operation is organised by two Jewish people. In the dream a voice was saying “this is a wake-up call, it is the Holocaust”’

The next dream gave a clear instruction:

‘Two men turned away from me, saying “We won’t talk to you, because you don’t have a soul.’

The dreams instructed a spiritual path and for Marika Henriques to come out of hiding and rejoin the Jewish community – this would be the final part of the healing for her to ‘become a complete person’.

In the final dream she is returned to a place where she is not hidden ‘a Jewish place’ where she joins in a dance with others who have all survived the terrible times.

‘I am in an open place. There is a lake. There are many, mainly elderly people there. Most of them went through terrible times in 1944, but they had all survived. It is a Jewish place. I am standing somewhat apart from them. A tall, old, good-looking man asks me for a dance. Somewhat reluctantly I accept. I am surprised how pleasant it was, how well we danced together.’