One of the interesting outcomes of reading ‘In Search of the Lost’ by Richard Carter is the impression of the very vivid way of life in the Solomon Islands and how this contrasts with life in the UK. One reason, Richard writes, is that in a way it’s easier to confront life’s mysteries there where you are constantly in touch with them. There are no modern conveniences to shield you from the elements, and death is not hidden but present – the fragility of life is taken for granted. In the Solomon Islands everyone gets everything whilst it is available, and when it isn’t then they do without.

When the Melanesian Brothers came on a mission to the UK, Richard Carter is reminded how endless choices can clutter us – there is so much distraction with less and less space for God. God seems to get pushed out being seen:

‘As one of the least seemingly exciting choices in a busy schedule. Yet we are lost without that centre, and how quickly we become forgetful of the reality of our faith. Again and again, I realise that more is less.’

Visiting Anglican churches with the group of Brothers, Richard Carter also becomes aware of how silence seems a thing to be ashamed of. He notices that there is seemingly a weighing-up happening through endless small talk in the church groups with pressure to make a good impression, or be coherent, or interesting, or amusing. By contrast in the Solomon Islands, it seemed that time belonged to people not people to time.

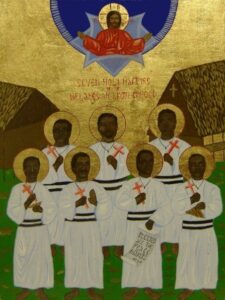

As he looks back on the events linked to the martyrdom of the seven Brothers, Richard Carter muses that the whole event was like entering into a great drama, but the drama was real although he kept hoping that it wasn’t.

‘And it went on day after day, so that you were inside it and outside it and longing for it to find a reconciliation. And then like a tragedy, I suddenly realised that all was changed unalterably and nothing would ever be the same, and there was no possible way of ever going back or bringing back, but that in the place you expected to find bitterness and dread, instead there was alongside the loss, a deeper humanity … You are face to face with what you are – naked as it were, without pride or delusions, but human, and present – and you are not aloe but there are others there with you, and strangely you are no longer afraid.’

The graves and memorials to the seven martyrs